"And when they sit down to have a chat...”

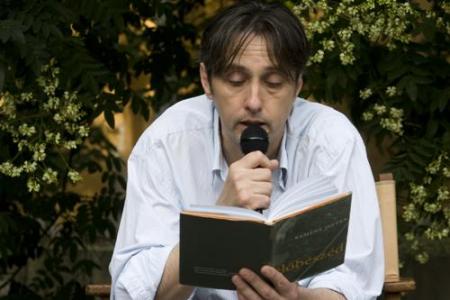

An interview with poet István Kemény from faraway Berlin, Germany, about his conversation book created in cooperation with Attila Bartis, as well as his novel, family, culture, future. About the Essence.

When "Friendly Stranger" (original title: "Kedves Ismeretlen") was published, you got to read about 'István Kemény, known primarily as a poet'. Why does a 'primarily poet' write a novel?

Why does a 'simple' poet write a novel? Let's say because Dezső Kosztolányi did. I don't really know. Maybe because I failed not to write a novel. I wrote my first poem at the age of eight but my first prose came only one and a half years later. You need to be mature for prose.

I'm not exaggerating when I say that the most anticipated book at 2009's Book Week was Friendly Stranger, maybe because there were no István Kemény novels before. What are your thoughts on the book since then, almost two years later? Were you surprised by its reception.

Yes I was. I didn't know my novel was the most anticipated work at Book Week, but I was pleasantly surprised. I thought the expectations regarding my book had been positive, but then, I realised they hadn't been. Not even neutral. Sort of dejected. The starting point of the reception wasn't 'okay, here's a book titled Friendly Stranger, let's see what it's like'. It was more like 'this is a poet's novel, let's see how bad it's messed up'. And it's may fault. It seems, with my ('primarily poet') career, I wasn't able to create the ideal atmosphere for a book's birth: stroller, cradle, peaceful family, etc. I couldn't convince the literary craft, the readers, the book vendors, that I am trustworthy, that although I'm 'primarily a poet', when I write a novel it is a real novel not only an experiment in prose. A reading that is worth putting into the shop window. So I was reflecting insecurity and so did the novel. (There were numerous reviews pointing it out.) I have friends that started to read it only now, two years after it was published. They were simply afraid of a letdown. Maybe because of the reluctant reception too. And there are those that liked my poems and they felt I cheated on them with prose...

They say there's as many readings as there are readers. How do you relate to Friendly Stranger since its release, after maybe rereading it a couple of times? In all, can an author be satisfied with their work or are there things that you'd like to change.

I'm not satisfied at all. I originally included a number of storylines that can be resumed. I wanted to tie my next novel to Friendly Stranger. It's meant to be continued. On the other hand, I see the mistakes too, I do take the reception seriously. The most significant observation to me is that I should've put more emphasis on the narrator – as a role. Not by much, only a couple of pages maybe, but with strong emphasis. Lyrically even. A romantic lyrical self-confession in a couple of pages is absolutely okay in an almost 600-page novel. In regards to being satisfied, I don't know if a novelist can be pleased with their own work. With me, it's different all the time. Sometimes, I'm sick of my early poems, and then the next time I read it, say a year later, I don't see what my problem had been.

Concerning the novel's setting – to be honest, Tamás Krizsán's character was the one that really caught my attention, althogh he seems to be the least dominant personality in the story. In spite of all their literary studies, most readers identify the narrator, in this csae Tamás Krizsán, with the author. What do you think about this? How does the author relate to his novel's protagonist?

I'm glad the protagonist-narrator caught your attention despite being 'the least dominant', only because Tamás and me, we have much in common. Other characters also have similar features but Tamás has the most. Let me be honest here too – I can absolutely understand the readers' attitude. I too, have a person in me that is curious, that is hungry for gossip and although I do know all the novelists' tricks to disguise themselves in their stories, how they divide themselves among the characters, how they confuse the clues, so that the nasty, nosy reader can't find them, when I'm reading a book, I'm looking for the author too, from Dostoyevsky and Gárdonyi to János Háy. One review states that Friendly Strangers is filled with self-hatred. This is unfortunate because that wasn't my aim. Sometimes cruelly, sometimes sadly and sometimes with an excusing humour, but eventually I always wanted it to point towards love.

Your novel offers a kind of a posterior insight into a couple of decades of Hungary before the political change. What role do you think Friendly Stranger will play in today's public thought.

To think that any novel can have an effect on public thought today, in 2011, I would need serious amounts of self- and public confidence. Although I can imagine it happening. And if I try harder, I can imagine my book having an effect. But I want it to be a positive effect... a charitable one, please. Anyway there's a narrator in Friendly Stranger so that someone from here and now can address the present and future (!) readers, and tell them about the times before the change. That is, being in a greater perspective, being more accurate, so that they realise the past phenomena that are still here today. So that they understand for instance why us Hungarians hate ourselves so much for things we could love ourselves for.

I don't think there's an easy way to ask you good questions after your converstion book with Attila Bartis, titled "Whatever You Can Talk About" (original title "Amiről lehet"). Although the two of you have been close friends for decades, that work shows that you still have surprises for each other through new information and experiences. How important is friendship for you in regards to creativity?

Practically, because you can show your unfinished poems to your friend and you can trust their opinion. Or even your novel. That is a lot of help. Thank god, I have friends like that and I hope they consider me such a friend as well. Whatever You Can Talk About is different in that, being a dialogue, it shows how a friendship works. How do friends talk? What's the structure, the dynamics of a friendship like? How does the mutual ideology, opinion of two friends come into existence? Or they, who really understand each other, how do they still misunderstand each other, how do they realise this and how do they treat it together. Regardles of the dialogue's topic, a reading like this can be useful to others.

What about family? Both of you talk a lot about your families, your parents.

Family's role in creativity? To me, it is extremely important. There are novelists who are able to create a whole world from thousands of angles. Shakespeare for instance. And there are those that work exclusively with their own point of view. They have to look for everyhing from that lone angle, travel to the object, seeing and observing it from everywhere but still from one angle at a time. They need a solid base. Or a plane. A family can help them a lot. One such writer is Gabriel Garcia Márquez. (Although one such solid point can be – catachresis though it may be – Proust's taste of madeleines, meaning, it doesn't have to be a family. Even a taste is enough if it's the starting point of something bigger.) Maybe there aren't any more kinds of authors, just these two. I'm a member of the latter category. I feel relaxed, justified having a family whose history I know more or less. I know where I came from and where I can take off from as far as I can.

Do you think that besides getting to know the other, the book can be used as a tool for self-recognition? What impressions did you have rereading the dialogues?

All good converstions make you realise something new about yourself. And this bookful of conversations were really good. It wasn't easy but it was worth it. The book is founded on two interviews, previously published on litera.hu years ago. This original version included a sentence by me about patriotism for example. Writing the book, I had a hard time expanding this part. Something was missing, but in the end, I realised what I'd wanted to say. So I wrote that I could not die for my country. This really isn't odd in 21st century Europe and most people probably think the same way or don't even bother, but for me to admit it, I had to take a real deep breath. I mean it's honesty. The book's title is no accident. This is something you can talk about.

To me, it's a really interesting experience to read the conversations between two such significant poets. How do you think this work will affect your role in the literary life?

Well I can only speak for myself, although I don't think any of us wants to be some kind of a star poet. Myself, I believe that your literary role is prepared by what you have done, and such a conversation book can be released because our previous works made it justified. Of course, it will affect our place in the literary craft, but I have no idea how and I don't want to know. It's not for us to decide. The literary craft will do it for us, and that is made up of a village worth of sensitive personalities. If uncle Pista and uncle Attila keep their houses clean, drink responsibly, have a peaceful family, work hard, they will like them. And when they sit down to have a chat at the tavern, some will surely listen in.

You touch on many themes in the book, but it seems Transylvania and the related, not exclusively cultural experiences have a central role. Does this have any special significance besides the fact that Attila Bartis was born in Târgu Mureş?

You can't ignore that. Neither Târgu Mureş nor Lăzarea where Attila's father is from. We spent a lot of time there, the two of us and with others too. And with László András whose first novel ("Diary of an Ursologist", original title "Egy medvekutató feljegyzései") was published last autumn. He's mentioned in the book numerous times. We had many many conversations in Lăzarea, that had a significant effect on the ones published in the book. (And we also cleaned the loo as a threesome, which to some extent can be called a cultural experience from a certain point of view.) What is so significant about Transyilvania, and Székely Land in particular? The same reasons why writing a novel is important. There is something about it I can't adapt to. You leave Hungary at night and get off the train in the morning and you're at home. Being at home at the end of the world is an experience you don't feel anywhere else in Europe. Maybe Russians feel like that on the shores of the Pacific Ocean. A sense of space. Freedom.

Speaking about culture and the literary scene, what do you think about the wars in Hungarian intellectual life? What experiences do you have in regards to today's cultural environment?

No surprise, mostly bad ones. It really is close to what a war is like. But it's a strange kind of war. I don't see how it will end, none of those involved seem willing to even win it. Because if you want to defeat someone, if you want to break someone's neck, you do have respect for them. You realise they exist, and they have a neck and it is important for you to have that neck broken. I can't see this here. Only mutual disdain. Everybody's talking through the other like they weren't there. All I can see is that in the end, the worse it is in this country the better because the sooner people realise that they can go and be an au pair in London, a full-time relative in Israel, a doctor in Sweden or not even physically leaving just staying here escaping to the inside, quitting culture and independent thoughts and finally disappearing in absolute emptiness. Being a normal person. A consumer. It seems intellectuals just quit spiritually. I feel this way but I just can't believe there's no way out. For, surprising it may be after what I just said, if I disregard these wars, we have a living, strong culture here. Hungarians are said (by Hungarians) to be mad at the rest of the world because it doesn't appreciate them. But it's still better to be mad at the world than ourselves. As a result of this anger, the will to live up to expectations, the ambition, this restless heart, as well as the vast amounts of talent, mental potential, healthy sense of trends and self-irony, that lives in Hungary, there is (yes, it does exist!) a powerful contemorary art scene, a vivid theatre and major literature.

A couple of weeks ago, your daughter, Lili won the György Petri Award. How does it feel to see your daughter in the same field? Do you give her any advice or is this independent of the traditional father-daughter relationship?

Well, it isn't easy to get used to it. I didn't mean to make her a poet for sure. Of course, she saw that literature does have significance at home. As for advice, through the years, I have voiced my opinion to many poets and novelists and there were hobbyists among them, really anyone that honoured me by showing me their poems. I did tell offensive things but I never told anyone to stop writing. It's not my decision. I can be wrong. However, my daughters could have been exceptions if I saw that they had no talent. Fortunately, this is not the case.

Not only does your daughter write poems, she also plays the guitar (she calls it "muddling") in the band Kisszínes. What do you think about that?

Her and Zsófi, my younger daughter (who just started to get seriously into poetry) are the two members of Kisszínes. I really love Kisszínes, but their mother is the number one fan. Fortunately, others like them too. Some 20-30 year old alternative musicians discovered them on Youtube and called them to perform at the Day of Hungarian Song, and they became the youngest artists of the event in 2009. I was pleased to see this as a kind of a feedback that we aren't the only ones who think they're talnted. I was a bit worried about Lili. I was afraid of people thinking that she's successful only because of me. But in the world of popular music, no one really cares about the father of Kisszínes. Only the songs matter.

Answering Attila Bartis' question on when you had written your first poem, you said: "When I was eight. I wrote two, and I realised I'm good at this poetry thing. So I stopeed doing it. Why bother?" You also mentioned it earlier in this interview. How about today? What are your plans? Another novel? Poems?

Both of them, I hope. I have a number of new poems and lots of printed notes for my next novel. Two books. One thin, one thick. That's enough work for the next couple of years.

And why are you doing this online interview in Berlin? Are you on the run? Or are you looking for the right creative circumstances?

A relaxed creative process is very very important. No, I'm not on the run at all. I was awarded a one-year DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst) scholarship in Berlin. This has to be the largest scale and most generous scholarship in the world. Attila Bartis had it three years ago, as did Péter Esterházy, István Vörös and many Hungarian and non-Hungarian writers and other artists in previous decades. I try to play on it as much as I can. I have a couple of months left, then I'll go home.

In conclusion, what do you think about the young people in their teens and twenties today that are your daughters' generations. Do you have any special observations, experiences regarding their reading practices?

A frequent scene from the infancy of our daughters on is when me and my wife meet our friends who desparately tell us that their children, nephews, nieces, grandchildren etc. don't read. They say those born after 1990, just don't read. They don't read anything at all, and the world will end. At least the world we lived in. This used to be and still is valid. Fortunately, there are things that help these generations: Harry Potter, blogs and such. It seems literature doesn't fade out, it just moves to the internet. Today, I think, a poem will reach more people in a poetry blog than twenty years ago in a periodical or in a book. So I was afraid doomsday was coming but that doesn't seem to be the case. There's a new talented generation growing up that is reached by the Essence online.

Facebook-hozzászólások