The First Christian Renaissance

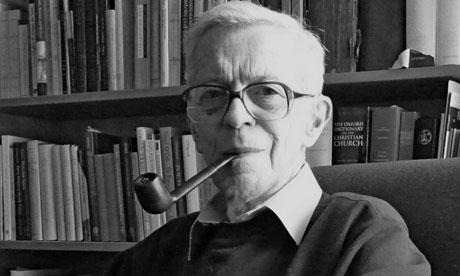

In this world, you can't really talk about the centuries following Jesus Christ without mentioning Saint Augustine. Whatever questions you may ask about the second part of ancient history, Augustine will have at least one answer for it. Published in 2010, "The End of Ancient Christianity" by Robert A. Markus presents this very well. The author of Hungarian origin who passed away this year, previously published a work that also takes the reader to the early medieval history of Christianity, titled "Gregory the Great and His World".

The title of "The End of Ancient Christianity" suggests something that is close to its conclusion, to which some would say: "What? Aren't we the heirs of ancient Christians? Don't we belong to the same spiritual community that was formed into a church by Christian faith and the certainty of Christian teachings?" The author is looking for an answer to similar questions in this work but instead of the modern man, he focuses on the point of view of 5th-7th century Christian people and their questions, uncertainties and commitments.

Citing numerous works of specialized literature, Markus analyses Christianity's relations to its own past (full of martyrdom) and present (the ways to keep faith without taking sacrifices of ultimate renunciation) in an era of relative religious peace following the issuing of the Edict of Milan. How did the Christian community try to build its own identity and everyday life as a result of the new circumstances? How did it settle surrounded by an old and alien culture with strong roots?

What did it mean to have a Christian identity in such a mixed environment? How could they live with the memory of martyrs inside a ring of pagan festivities? How could they genuinely live and relate? What are the points of reference in a world without an elaborate system of everyday life, holidays and religious truths? How can a vast number of Christian groups form unity? What does it mean to be a Christian? The concept of conversion came to the front, the demand for a practice that is well separable and traceable at the level of everyday life as a Christian way of life. Moreover, there were issues in regards to the relations with the pagan past and pagan contemporaries. A way had to be found to separate acceptable and adoptable elements of that culture from those that are only bearable or should be uniformly objected, while living next to it as a part of the same society. Everyday life is problem-free as long as true Christians view theatre, circus, races as ways of entertainment instead of rites of a condemned religion.

.jpg)

These are the disturbing and urging questions of an era of uncertainty in which the answers were crucial and unavoidable. And there were those who said no to everything surrounding them in order to stay clean, perfect and sinless. However, the forms of seclusion and self-restraint, the ways to find spiritual completeness weren't clearly outlined. Can you completely experience faith in the city with your family or should you choose seclusion? Ascetic discipline was a typical topic of the era's disputes. Opposing it were Jovinianus and Helvidius while Jeremiah supported the idea. Some, including Augustine, were reasonable and took the middle course while others like the Donatists wanted to extend perfection and immaculate cleanness to the whole church. This concept made way for three problems: marriage, the teachings of grace and a dual measure that would have divided the community into a religious elite and a group of common Christians. Markus' work includes letters and quotes of debates that show the topicality and significance of these issues, while at the same time the reader can witness the unfolding of Western spirituality.

The book also discusses the development of religious orders, their theoretical and practical differences, the debates which created them and where they found inspiration during their formation as well as their effect on the everyday life of ordinary people and their culture. Markus also shows their role in making the age of reading and interpreting the Bible succeed ancient culture. The fact that while Christianity tries to clear its identity in Rome, North Africa and Gallia, a religious and cultural takeover takes place in time and space is also discussed. Not only does the clarification of festivities and their binding to particular days in the calendar have spiritual reasons as it also accomplishes the embedding of everyday life differing from pagan practices into constant and solid frames. A change of not only time but space also becomes a significant ambition. Pagan sacral spaces get substituted by topographic elements honouring the remains of Christian saints which tears up the borders between towns previously thought to be unbreakable, and washes away the traditional differences between inside and outside as a result. While people tried to live as true Christians and genuinely adapt to the past hallmarked by martyrs, they also created a future hoping for continuity where they tried to achieve the homeliness and naturalness of experiencing faith.

Markus uses the works and theoretic debates of the authors of the era to present the questions of that world as well as the future realised in the answers, that is, our legacy.

Robert A. Markus: Az ókori kereszténység vége. Catena Monográfiák sorozat 11. Budapest, Kairosz, 2010.

Facebook-hozzászólások