The Space to Live

The title of the 12th International Architecture Exhibition in Venice is the evergreen phrase related to man-made space, "People meet in architecture". You do not usually think about this fact, probably because of the twisting drive of consumer society. It is somehow natural that people meet in built environment and sense its atmosphere. Moreover, if you think about built spaces, be it sacral or industrial, your dialectical relation to them is almost exclusively oriented by perception. The practical aspect by which the architect includes the human demands of application in the imaginary space as early as the birth of their visions, seems absolutely natural. Emphasising the role of practicality is necessary because besides it resulting in a different relation, not only is star architect Kazuyo Sejima, this years director, the first female trustee in the history of architecture biennials, but she also is a practising architect. SANAA, her Tokyo-based studio, founded in cooperation with Ryue Nishizawa, won the Pritzker prize (the Oscar in architecture) in 2010. The solo works of the two Japanese architects are exhibited at the venue of the biennial as well. However, I'll review the Hungarian pavilion first, including the project of Borderline Architecture.

The project led by Andor Wesselényi-Garay and Marcel Ferencz is made up of three parts; black and white movies, hundreds of drawings, and pillars made of 90 kms of strings and pencils, hanging from the ceiling. The coherence is formed by the architectural drawing based on a personal story.

According to Andor Wesselényi-Garay, the story goes like this: "In 2009, there was an architecture conference in Zagreb, and Alvaro Siza was the last lecturer. After his presentation, the architect of the Hungarian pavilion Marcel Ferencz stood in line for an autograph. When it was his turn, he handed over the monograph and said 'A big graphic please!' Through the natural tension of the situation he blended the words 'autograph', 'biograph' and 'monograph' all into each other. Siza looked at Marcel, smiled and said 'You look like you do sports, so you know what? I'll draw you an athlete arriving at the sports centre.' He was still smiling when he took the marker and outlined a running figure with just a coulpe of lines. The air stood still around him while he was drawing. The moments showing the artist at work, created an astonishing atmosphere. There was magic in the small sketch, especially since it was created in front of a crowd petrified by the surging experience. Not only did it make clear that architects still draw but also that the way they do it is interesting."

Inspierd by this experience, the duo created an hour-long film documenting architects while drawing. Besides spying on the silent tricks of the trade, their work also shows the verbally uttered differences between brain-controlled sketches and perfect computer-made layouts lacking any emotional content. One such difference for instance is the fact that a software cannot calculate the inspirational bases that is needed to make a building look similar to Henry Moore's sculptures. The software creates plans while a sketch is inspiration put on paper. Still, its autonomy is questionable.

Borderline Architecture describes the importance of drawing like this: "The exhibition at the Hungarian pavilion defines LINE as the starting point of architectural thought as opposed to HOUSE, thus presenting the primal state of architecture." The reflections related to the drawn line are the immensely spectacular pillars installed at two indoors and one outdoors space of the pavilion. The pillars consist of more than 30,000 pencils, part of which came from a collection addressed to the teachers' union. The labelled pencils evoke the spirit of drawing through anyone's pencil from a wide range. The thousands of personal items are installed in a special manner in the apsis of the pavilion.

The concept of Borderline Architecture overwrote the event's original title "People meet in architecture" in a witty yet convincing way to "People meet in drawing".

Besides the line abstraction of the birth of space, the statement on meeting can be interpreted in many ways. The Belgian national pavilion presented an interesting approach to the meeting of man and environment. The exhibitors focused on the damages done by humans on the pieces of furniture inside built spaces. The surfaces showing signs of use, cuts, breaks and wear were recontextualised in a profane and sacral system of references in art history. This is how three doors in monochrome style or three used black rubber carpets turn into a triptych.

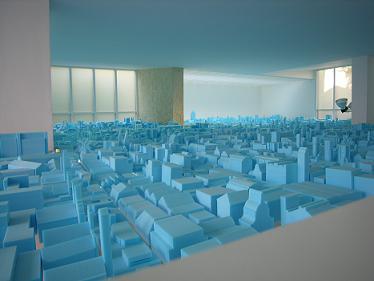

The Dutch on the other hand aimed at the partial or possible occurence of the meetings taking place in man-made space. The sentence under the vinyl of a shadow building on the facade of the pavilion designed by Gerrit Rietveld reads: "The pavilon was built in 1954 and is in use for 3.5 months a year." Inside, there is a suspended ceiling of a floating city maquette consisting of blue buildings.

The Russians also focused on the possibilities of abandoned spaces. Their national pavilion shows the photo documentation and the layout plan of the rehabilitation project of six factory buildings as well as a circular panorama painting of an idyllic urban environment.

Instead of exploiting the possibilities at hand, the group of young architects from Romania presented the audience with a subjective sense of space. They built a snow white, single-room building with an area of 94.4 square metres. Only one visitor was allowed inside at a time, while those outside could peak inside through small holes. The 94.4 square metre area refers to the living space per capita in Bucharest.

The Canadians displayed the numerically expressible spacial presence of the subject through the futuristic visions of Philip Beesley. The interactive, interconnected and elegant robotic creatures at their pavilion were set in motion as a result of various chemical processes around them. And who knows, maybe it isn't too far away in the future when the space around you reacts to how you feel.

The Australian vision focused on the near future as well. Their two-story pavilion featured perfectly photographed 3D 'films' taking us Down Under now and in 2050. Watching through special goggles, the stereoscopic effect of these works is so perfect that you feel you need to move your shoulders when the birds-eye view suddenly changes and you fly over the Opera House into downtown Sydney. The present views and future visions of these films titled "NOW and WHEN" appear already on the path leading to the pavilion.

The Wim Wenders movie shown in Arsenale also uses 3D technology to impress the visitors. This time, Wenders' work does not deal with man, the protagonist of meetings, but an anthropomorphed building, a work by SANAA, the recently erected Rolex Learning Center in Lausanne. In a humming female voice, the building tells about all the cultural values inside her, the changes taking place with the passing of time, while urban europid students use her every corner. Eventually, a traditional Japanese kimono-clad female figure appears in a way that only you can see her.

Two very special projets of space sensing were related to the timely instantaneity of seeing and hearing. The visitors were dazzled by one of Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson's famous water projects installed at the enormous, pillared ninth hall. Hung from the ceiling, there were rubber pipes twisted by water pressure and illuminated by strobe light from above. The light glittering on the drops of water squirting from the dancing pipes created an effect of thousands of rolling beads.

Canadian artist Janet Cardiff's sound installation titled "The Forty Part Motet" dealt with the acoustic sensing of space. She recorded the voices of the forty singers of the Salisbury Cathedral Choir one by one, while they were singing a renaissance choral work by Thomas Talis. Then, she played all the voices on different speakers, which allows the listener to experience the piece from special positions, even the singers' 'point of listening'.

The Arsenale was the venue of the most tragic and most successful exhibitions of this year's biennial. The former was presented by Croatia with the title "Floating Island". It was a pavilion built on a 32-ton transparent-structured tow-boat welded from steel nets. The structure was floated all the way to Venice on the Adriatic Sea but upon arrival, it collapsed. Despite the tragedy, the Croatians presented and gave away pallets of photographs and posters showing the phases of building the installation.

This year's Golden Lion prize was won by Bahrain's project "Reclaim". The pavilion was made up of actual-size fisherman's shacks furnished with carpets and pillows. The shacks arrived in pieces directly from Bahrain. It wasn't just a regular exhibition but also a way of demonstrating. The island has been inhabited for 9000 years, but these traditional shacks and the fishermen owning them are being pushed out of the scenery by the high-speed urbanistic change that includes the building of luxury apartments on the island's beaches. Moreover, not only did the reorganised city structure eliminate the public space related to their profession, but it also denies the free access to the sea – a right the fishermen and their ancestors had for thousands of years. According to the exhibitors, the project presented at the pavilion is only an initiave, as the state of affairs on display is only the tip of the iceberg, and what follows is something the local political and economic experts as well as the general public has to pay attention to.

Interviews with locals torn out of the structure were also screened at the pavilion, and according to the plans, the university students involved in the research are going to use the workshop material to create a documentary.

One curiosity of the exhibition was that after the long preparation, out of the 54 participating countries, the Venezuelan pavilion stayed closed.

Facebook-hozzászólások